Published on

Updated on

Published 2/17/25

Story contact: Deidra Ashley, CVMMarCom@missouri.edu

Photos by Karen Clifford

Every year, sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) claims the lives of thousands of people with chronic seizures. While the exact cause remains unknown, researchers believe disruptions in autonomic functions — like breathing and heart rate — may be key contributors.

At the University of Missouri, Associate Professor and researcher in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, Carie Boychuk, PhD, and her team are working to unravel how epilepsy interferes with these processes in the hopes of one day developing life-saving interventions. The research is a natural fit for Sandy Saunders, PhD, a Florida native who joined the Boychuck lab in 2024.

Saunders was recently announced as a member of the inaugural cohort of NextGen Postdoctoral Fellows, a program that supports her work in the Boychuk Lab for the next two years. Through the opportunity, she’s gaining the resources, mentorship and collaborative opportunities to push this critical research — and her career — forward.

Seizures and signals

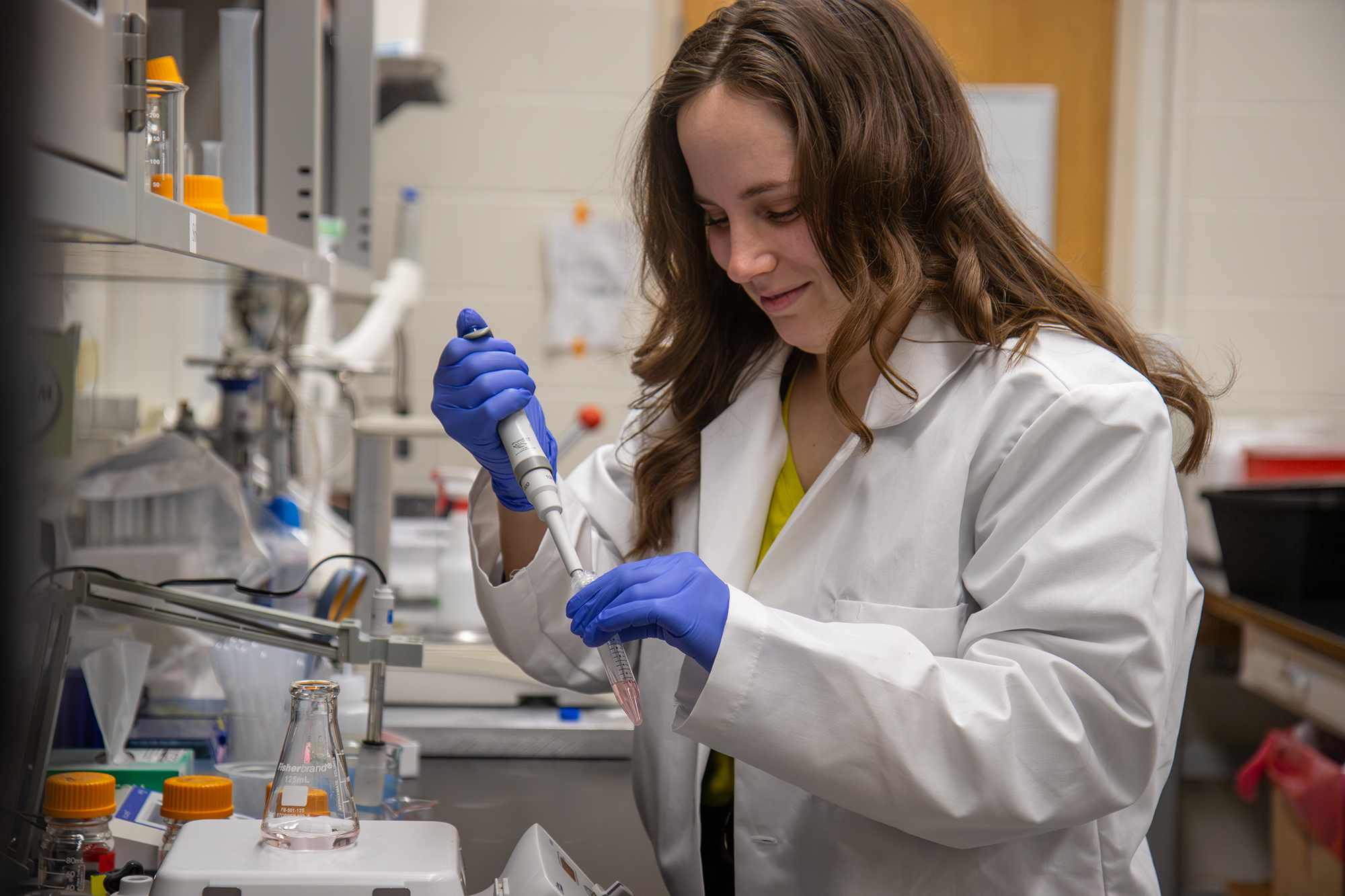

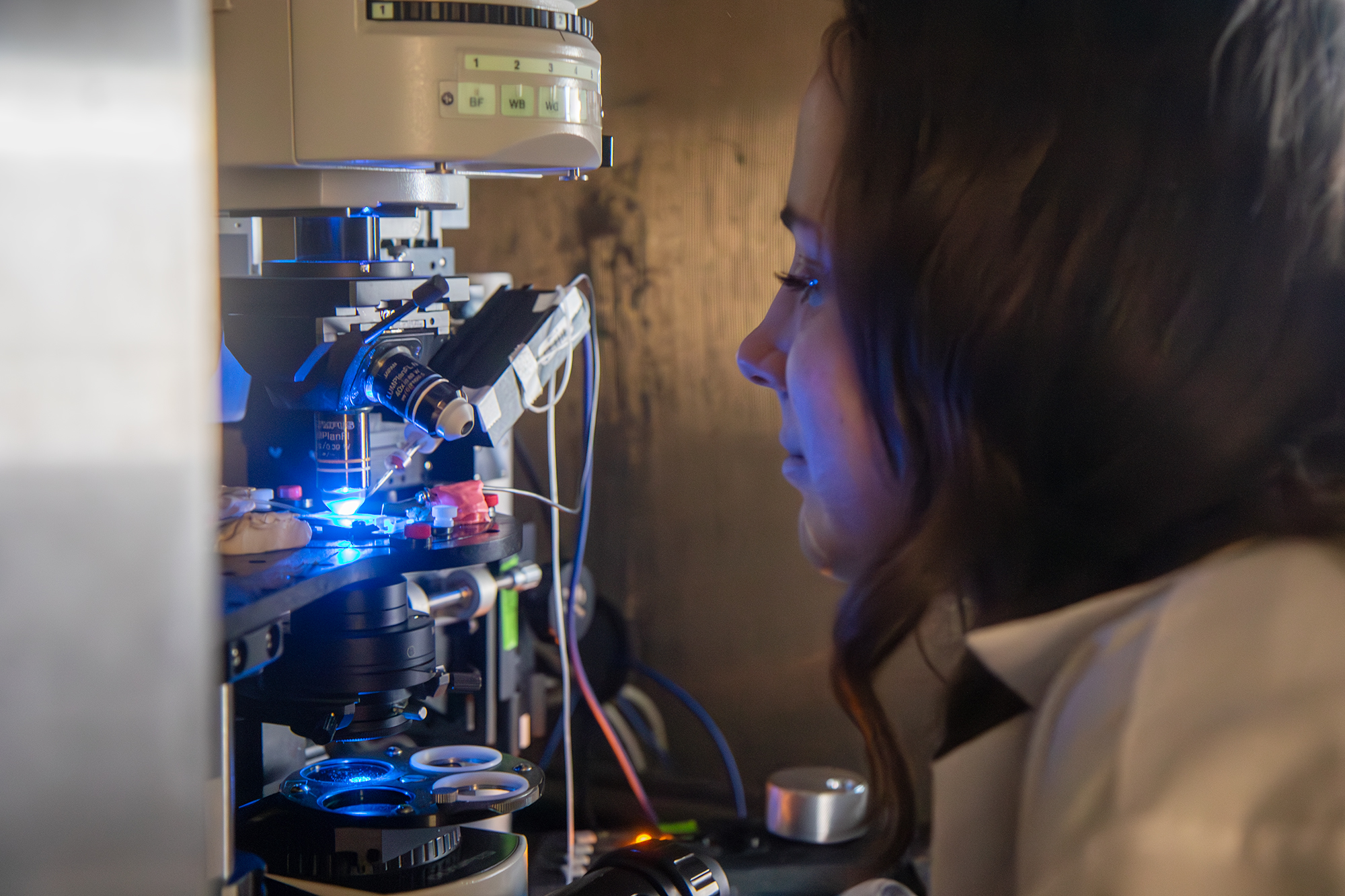

Using a mouse model, Saunders uses techniques, such as electrophysiological recordings, to measure heart rate, blood pressure and breathing patterns. These recordings allow them to track changes in autonomic function in real time and assess how stress-related disturbances might trigger fatal cardiorespiratory events.

In addition to monitoring physiological responses, the team is exploring whether specific neural circuits are responsible for these exaggerated reflexes. By using targeted viral approaches, they aim to pinpoint dysfunctional neural pathways and determine if they play a causal role in SUDEP. The ultimate goal is to identify whether these autonomic disruptions are a direct cause of fatal seizures or simply a secondary effect of epilepsy. Saunders said if a specific reflex pathway is found to be a key factor, existing FDA-approved drugs could be repurposed to block these exaggerated reflexes and prevent SUDEP. She also hopes the research could lead to clinical screening tools that assess autonomic function in epilepsy patients, helping identify those at higher risk and allowing for earlier intervention.

Building confidence, breaking barriers

When Saunders joined Mizzou in 2022, she was eager to return to an R1 research institution — one that would provide the resources and collaborative spirit essential for groundbreaking work. She said what she found exceeded her expectations.

“Before I came here, I often felt isolated in my research,” she said. “At Mizzou, and especially where I work now on the third floor of the Dalton Cardiovascular Research Center, there’s such a strong intellectual community of experts who support you. It’s nice to know I can go to these people at any time and ask for advice.”

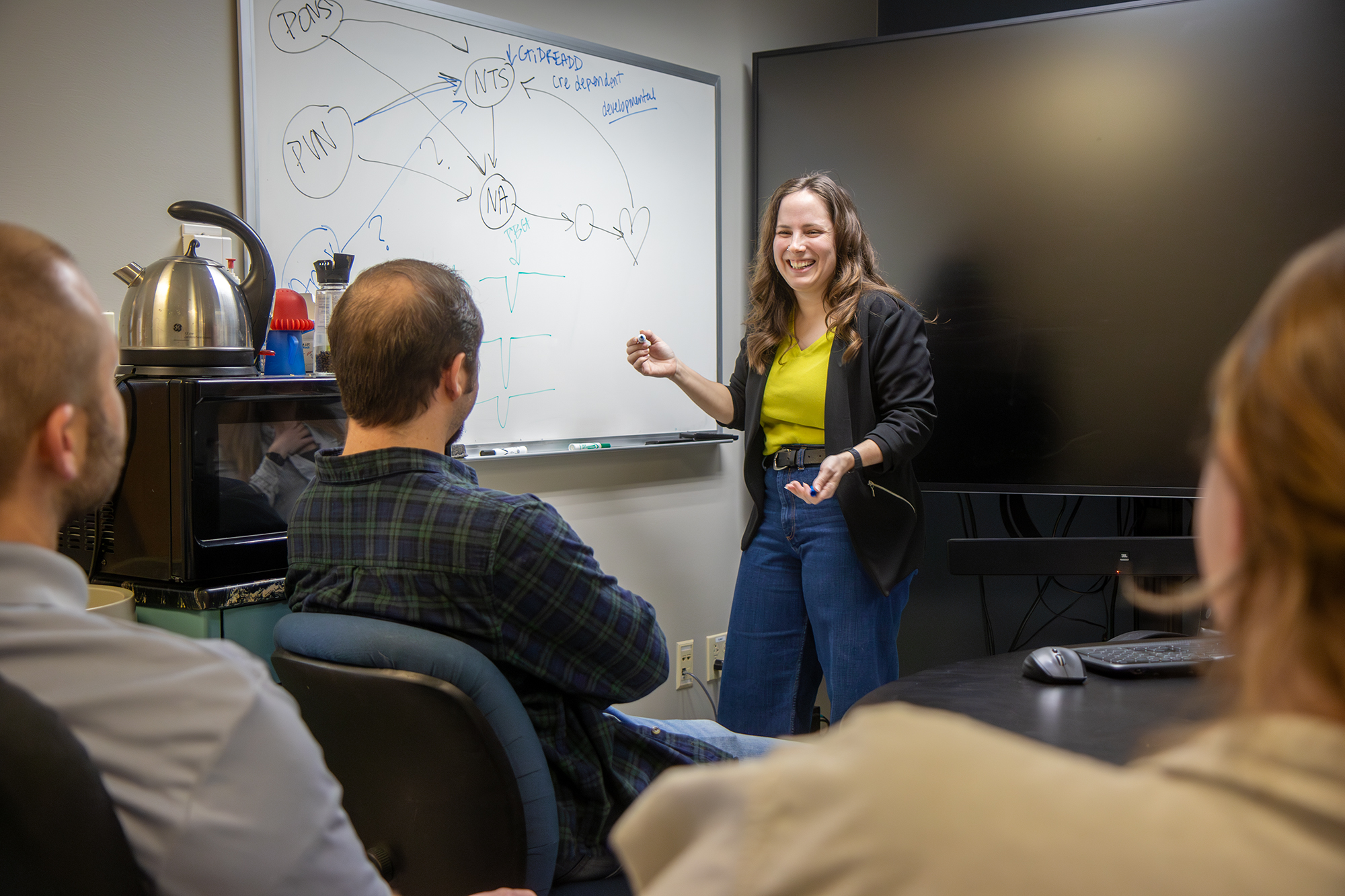

Saunders credits her mentor, Boychuk, for fostering an environment that helps young scientists thrive. “Dr. Boychuk is an awesome mentor,” Saunders said. “She really pushes you to succeed and actively seeks out ways to support postdocs and help us grow. She’s given me so many opportunities, and I’m grateful for that.”

One of those opportunities is the chance for Saunders to train an undergraduate researcher.

“A lot of postdocs don’t get the chance to train students,” Saunders said. “Being a mentor is definitely a learning experience but getting to watch my trainee learn new techniques and master them has been a joy and has given me a whole new perspective on my work.”

Saunders’ dedication to mentorship is just one example of how she’s growing as a scientist.

“Sandy is passionate about the work she does and is constantly thinking ahead to the next experiment,” Boychuk said. “She’s not only mastered the techniques in my lab with impressive speed, but she’s also becoming more confident — mentoring students, refining her presentation skills and understanding the broader role of academia beyond the lab. Postdocs like Sandy are the driving force of scientific progress, and her dedication ensures that we’re always pushing the boundaries of what we know so we can improve health for all Missourians.”

From pipettes to passing pucks

When she’s not in the lab, Saunders plays underwater hockey with the COMOdo Dragons, a local team she helped start. “Underwater hockey is a unique physical challenge because you have to keep holding your breath while moving,” she said. “It not only helps me de-stress, but it also fuels my curiosity as a cardiorespiratory physiologist.”

She explained that the sport makes her think about how her body responds to changing oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. “I believe this type of exercise — or gentler versions of it — could be used in clinics to help treat a variety of conditions by strengthening the mammalian dive reflex.”

One of the most fascinating things about the body, Saunders said, is how different activities trigger different responses. Holding your breath underwater activates the mammalian dive reflex, which causes changes in the body similar to those seen in SUDEP—meaning it might actually raise the risk. Running, however, has the opposite effect.

With support from the NextGen Postdoctoral Fellowship and in collaboration with Boychuk, Saunders hopes her research will lead to breakthroughs in understanding SUDEP and improving long-term outcomes for patients in Missouri and beyond.